Burned remains, also called cremains, were various types of bones and teeth found on Steven Avery's and Barb Janda's properties. The bones were initially determined to be of a 20-25 year old human female and later were assumed to be Teresa Halbach's when tissue contained a partial DNA profile was recovered from a piece of bone matching Halbach.[1] The remains were initially found only in and around a burn pit on Steven Avery's property. Later more bones were recovered from a burn barrel on Barb Janda's property.

In season 1 of Making a Murderer Avery's defense suggests the remains were planted to frame Steven Avery for murder, but it doesn't specifically point the finger to Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department officers Andy Colborn or James Lenk, who the series ascribes most of the other allegedly planted evidence to. In season 2 Avery's postconviction attorney Kathleen Zellner argues it is not possible to burn a body in an open air fire pit to such degree. She argues Avery's nephew Bobby may have murdered and burned Halbach in a burn barrel and used the burn barrel to pour the bones on Avery's property.

Description[]

Discovery[]

- see also: Steven Avery’s burn pit, Barb Janda’s burn barrel

The first known occasion that someone spotted the burn pit where later the bones were found was on Monday 7 November, when Manitowoc County Sheriff’s Department officer Jason Jost was requested to feed all the dogs on the Avery’s Auto Salvage property. One of those dogs was Steven's dog Bear who lived in a dog house behind Avery's garage. As Jost fed the dog he noticed the burn pit.

The next day Jost again came near the burn pit when he was asked to relieve a Brillion Police Department officer for a break. The officer was on Steven Avery's property by the propane tank, next to the burn pit. As Jost arrived there he noticed a white object nearby the burn pit that he believed to be a piece of bone. Jost thought the area looked like it was used for a fire and recalled a witness statement about observing a fire on 31 October at Steven's property. Jost informed Calumet County officer Kelly Sippel, who shared Jost's suspicions about the white piece. When more suspected bone material was found a while later by DCI Special Agent Tom Sturdivant, a decision was made to inform the Wisconsin State Crime Lab. Once crime lab personnel arrived a sifting process was started to collect suspected bone material and sent it to the lab.

Forensic examination[]

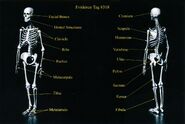

Initial forensic examination was done by forensic anthropologist Kenneth Bennett, who had received the bones, brought to him in a white cardboard box, on 9 November 2005, one day after they were collected. Bennett was requested to determine whether these bones belonged to a human or not. Upon opening the box, Bennett observed many of the bones were immediately and incontrovertibly diagnosable as human.[2] Further examination showed a part of the pelvis bone (the ilium) and a faintly developed linea aspera which strongly indicated female sex. Estimated age of the female was 20 - 25, but not older than that. Bennett further noted that there is no evidence non-human bones were present.[2]

A photo of the white box with bones delivered to the State Crime Lab by DCI agent Dorinda Freymiller.

The next day another forensic anthropologist, Leslie Eisenberg, also examined the bones from the same box.[3] Eisenberg's task was, again, to determine if the bones belonged to a human, develop a biological profile (sex, age, race, etc) and finally determine the case of death. In the box Eisenberg noticed many pieces that she identified as skull bone from a human.[4] A larger piece of bone which showed less fire-damage than most of the other bones was also observed and determined unquestionably human.[5] It was packaged and sent to the FBI for further analysis.

Based on the contents of the white box of bones Eisenberg concluded all bones were human and belonged to a female not older than 30-35 years of age.[6][7]

Bone from the back of the skull with internal beveling.

Based on the fact the body was destroyed by means of fire to obscure the identity of the victim Eisenberg believes the manner of death is a homicide.[8] In pieces of skull from the left side (cranial) and back side (occipital) Eisenberg observed two unnatural openings,[9] which she described as "internal beveling" - an opening that on one side of the material is small, but on the other is larger, like a crater, caused by something going through.[10] According to Eisenberg these unnatural openings existed before the body was burned.[11] The evidence suggests to her that the cause of death was a gunshot wound.[12]

Eisenberg believes Steven Avery’s burn pit was the primary burn site of the body because of several reasons. One reason was that at least a fragment or more of almost every bone below the neck was recovered in that burn pit.[12]

In February and November 2006 forensic scientist Ken Olsen received the skull bones with internal beveling.[13][14] Olsen examined the beveling and concluded it was consistent with a high energy projectile entering the skull.[15] When the internal beveling was analyzed Olsen detected the presence of lead.[16] On x-rays the lead was visible as small bright dots and most of the lead was concentrated in or on the beveling.[17]

At trial and appeals[]

2007 Steven Avery trial[]

The prosecution presented testimonies of forensic anthropologist Leslie Eisenberg, forensic scientist and trace evidence examiner Kenneth Olsen, forensic scientist and DNA analyst Sherry Culhane and medical examiner Jeffrey Jentzen to establish that the burned remains found in Steven Avery’s burn pit and the Barb Janda’s burn barrel belonged to Teresa Halbach, the manner of death was homicide and the primary burn site was Avery’s burn pit. According to Eisenberg the bones belonged to a human of the female sex not older than 30~35 years. Charred tissue on a piece of shin bone was examined by Sherry Culhane and yielded a partial DNA profile that matched Halbach's DNA profile to the exclusion of one in one billion people.

Eisenberg, Olsen and Jentzen observed entrance defects in two parts of Halbach's skull; on the left side and on the back. Using x-ray technology Olsen observed lead particles in and on the entrance defects. Eisenberg and Jentzen ruled the manner of death a homicide, caused by a gunshot. The shooting happened before the body was burned.

Eisenberg believed the burn pit was the primary burn site because a piece of almost every bone below the the neck was recovered from the burn pit. Tiny brittle piece of bone were only recovered from the burn pit and not, for example, in the Janda burn barrel.

The defense did not argue that the bones were not Halbach's, nor did they challenge the fact Halbach was shot. The defense challenged the suggestion that the Avery burn pit was the primary burn site, because only someone other than Avery would move bones to Avery's property. As an alternative burn site the defense offered a quarry pile about 0.43 miles (680 meter) southwest of the Avery property, where more burned, but also unburned bone material was recovered, particularly an alleged pelvis bone that showed charring to the same degree as the bones recovered on the Avery property. Though the majority of the bones were determined non-human, Eisenberg said the alleged pelvis bone may be human because of some of its characteristics. She described the bone as "suspected possible human".

The defense presented testimony of Canadian scientist Scott Fairgrieve to further their narrative that the bones in the Avery burn pit were planted. Fairgrieve testified that in his experience usually the place where bones were moved to had more bones than the location where the bones came from. Earlier, Eisenberg had testified that the bones found on Avery's property could be as few as 40% of the total body, or as much as 60% of the total body. Eisenberg also explained some parts of the bone could not survive such a fire and would completely vanish.

2016 - 2022 Kathleen Zellner appeals[]

One of Kathleen Zellner's experts, John DeHaan, a renowned arson forensic scientist, provided an affidavit for Zellner's 2017 motion. In it he expressed why he believes the burn pit was not the location where the victim's body was burned.

DeHaan does agree with the State's expert Leslie Eisenberg that the body was burned outside, in an open-field fire, but believes the damage done to the larger bones could hardly have been done in four hours, which he believes is how long the bonfire lasted.

Photos[]

References[]

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 10 - testimony of Sherry Culhane, page 162

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Summary of DCI case no. 05-1776

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 126

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 132

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 136

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 137

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 138

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 153

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 157

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 159

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 165

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Avery Trial Transcripts, day 13 - testimony of Leslie Eisenberg, page 166

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 15 - testimony of Kenneth Olsen, page 11

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 15 - testimony of Kenneth Olsen, page 16

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 15 - testimony of Kenneth Olsen, page 14

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 15 - testimony of Kenneth Olsen, page 15

- ↑ Avery Trial Transcripts, day 15 - testimony of Kenneth Olsen, page 26